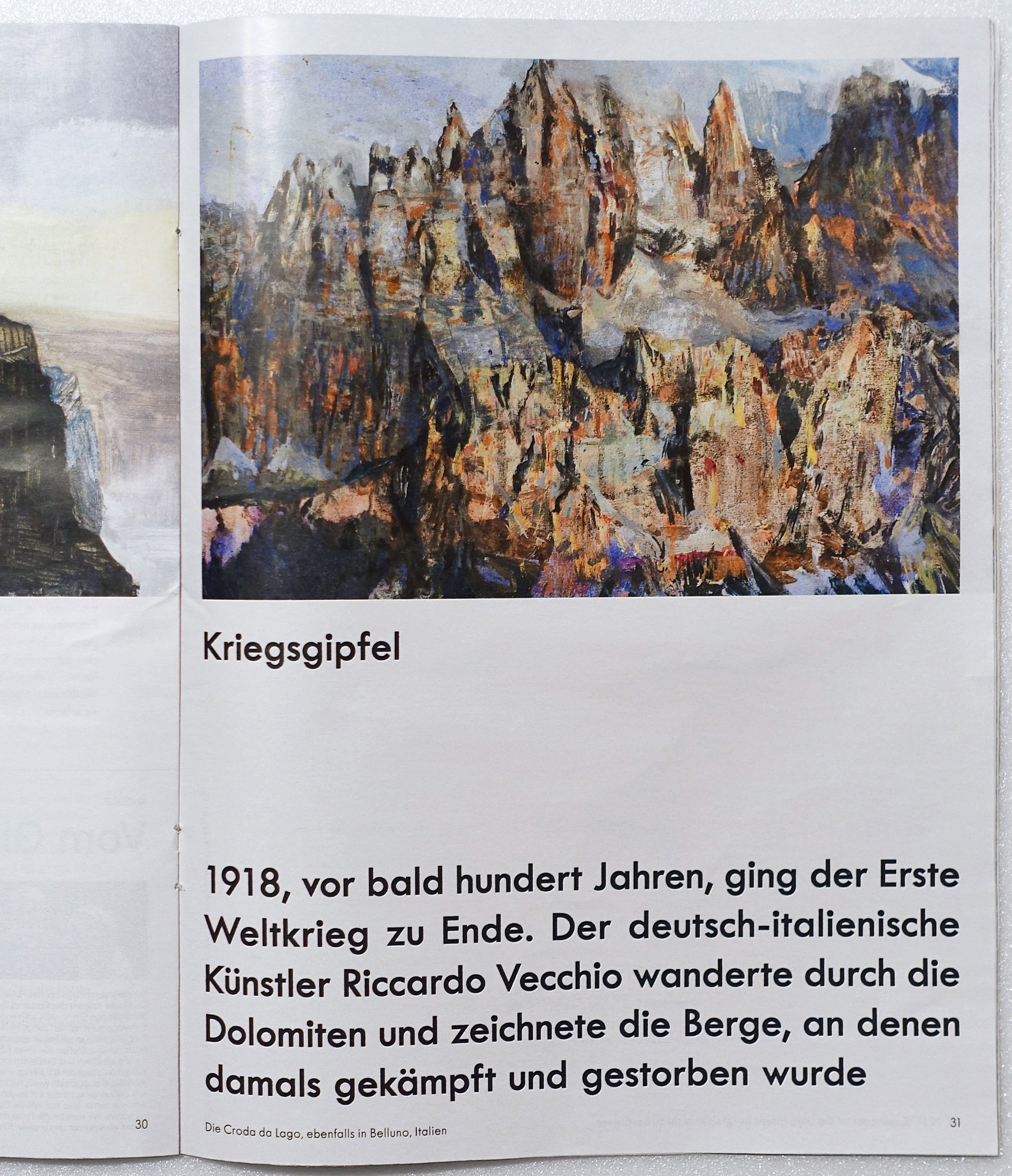

1918, vor bald hundert Jahren, ging der Erste Weltkrieg zu Ende. Der deutsch-italienische Künstler Riccardo Vecchio wanderte durch die Dolomiten und zeichnete die Berge, an denen damals gekämpft und gestorben wurde. Von Mohamed Amjahid

ZEITmagazin Nr. 53/2017 19. Dezember 2017, 17:23 Uhr

Ob Gabriele D’Annunzio am 9. August 1918, kurz vor Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges, ein Auge für die Schönheit der Dolomiten gehabt hat, weiß man nicht. Auf jeden Fall flog D’Annunzio, italienischer Poet des Fin de Siècle und Propagandist des Militärs, an jenem Tag über sie hinweg, er saß hinter den Piloten einer kleinen Propellermaschine. Zusammen wollten sie von Padua nach Wien – der Hauptstadt des Feindes. An Bord hatte D’Annunzio Tausende grün-weiß-rote Flugblätter: Kriegspropaganda. Doch der Text war nur auf Italienisch zu lesen, sodass die meisten Wiener ihn nicht verstanden. D’Annunzio war das egal, er hatte sowieso nur die eigene, kriegsmüde Bevölkerung im Visier: In der italienischen Presse wurde der Propagandaflug hinterher bejubelt, und fürs Durchhalten versprachen die italienischen Kriegsführer ihrem Volk die Annexion der bis dahin zur Habsburgermonarchie gehörenden Dolomiten. Am Ende haben die Italiener den Gebirgskrieg auf 4000 Meter Höhe gegen Österreich-Ungarn gewonnen. Der Preis: Hunderttausende Menschen starben durch Granatbeschuss oder Kälte.

Der deutsch-italienische Künstler Riccardo Vecchio wanderte im Jahr 2014, hundert Jahre nach Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges, wochenlang in den Dolomiten. In den folgenden Sommern kehrte er dorthin zurück, studierte Gipfel, Eisformationen und Bergwege, auf denen Maultiere einst Proviant für die Truppen transportierten. Sein Großvater Cesare war mit 18 Jahren in die italienische Armee eingezogen worden, wurde später von Österreichern gefangen genommen, konnte entkommen und floh im Sommer 1917 zu Fuß über die Berge nach Mailand.

"Ich kenne die Dolomiten von Ausflügen in meiner Kindheit. Ich bin dorthin zurückgekehrt, um das aktuelle Unbehagen in Europa zu verstehen", sagt Vecchio, 47, der seit zwanzig Jahren in New York lebt und arbeitet. Auch im Zweiten Weltkrieg wurden die Dolomiten zu einem Schauplatz des Grauens. Mit den schmelzenden Gletschern tauchen nun überall Relikte des Krieges auf, Vecchio fand bei seinen Reisen Einschlagkrater und Überreste von Bomben. "Angesichts des Aufkommens von rechtspopulistischer Rhetorik und Nationalismus überall auf der Welt sind diese Berge Zeugen vergangener Massaker im Namen von Machterhalt und Profit", sagt Vecchio.

In seinem Atelier in New York arbeitet er seit Jahren an den Ölgemälden. Detailversessen versucht Vecchio jeden Hang, jeden Felsen, jeden Gipfel so genau wie möglich nachzuzeichnen. Seine Mission sei es, die Erinnerung an das Grauen vergangener Tage für die Zukunft wachzuhalten, sagt er. Wer weiß zum Beispiel noch, dass am 13. Dezember 1916, an einem einzigen Tag also, Tausende Männer in Lawinen starben? Grenzen zwischen Ländern liegen oft in den Bergen, wo niemand wohnt. Es macht also fast keinen Unterschied, ob die Grenze ein paar Meter weiter hier oder da verläuft. Aber der Nationalismus lässt dafür Unzählige sterben.