The Embassy of Italy and the Italian Cultural Institute, with the Pratt Institute and Ivy University, invite you to an exhibit exploring the layered themes of memory, continuity, and remembrance as seen through the lenses of several generations of Italians. Artists Kikki Ghezzi and Riccardo Vecchio invest their works with the physical remnants and records of family memories and historical events.

In Ghezzi’s work, the importance of her connection to prior generations of strong women in her family is physically manifest in her use of heirloom linens, embroidered by her grandmother, that have been passed down as a dowry in a traditional cassone, and now serve as the literal support for her paintings. Paintings by Riccardo Vecchio explore the historical past, specifically the events of World War I, where the Italians fought in the Dolomite mountains and the Alps. As the mountains suffer the effects of climate change, they are disgorging their history and souvenirs of the past, to reveal details of the lives of people who were engaged in combat there in 1915 and as World War I unfolded. Fragments of memory, and fragments of time, the frammenti referred to here, are captured by these two Italian artists to help us understand the longer continuum of life, and reflect the concerns of their generation as culture responds to an increasingly hectic world.

LOCATION

Embassy of Italy

3000 Whitehaven Street NW

Washington, DC 20008

Riccardo Vecchio paints the mountain ranges of the UNESCO World Heritage sites in the Dolomites and the Alps. These paintings transport us to remote mountain summits that are vividly present in history. Joining a tradition of painting the mountain as a sublime obstacle in nature, Vecchio emphasizes the struggle of man against nature. J.M.W.Turner depicted the crossing of Carthaginian General Hannibal when he traversed with elephants, and Jacques-Louis David painted where Napoleon crossed the Saint Bernard pass, with rocks inscribed to record previous travelers and triumphs, but Vecchio takes other memories as inspiration.

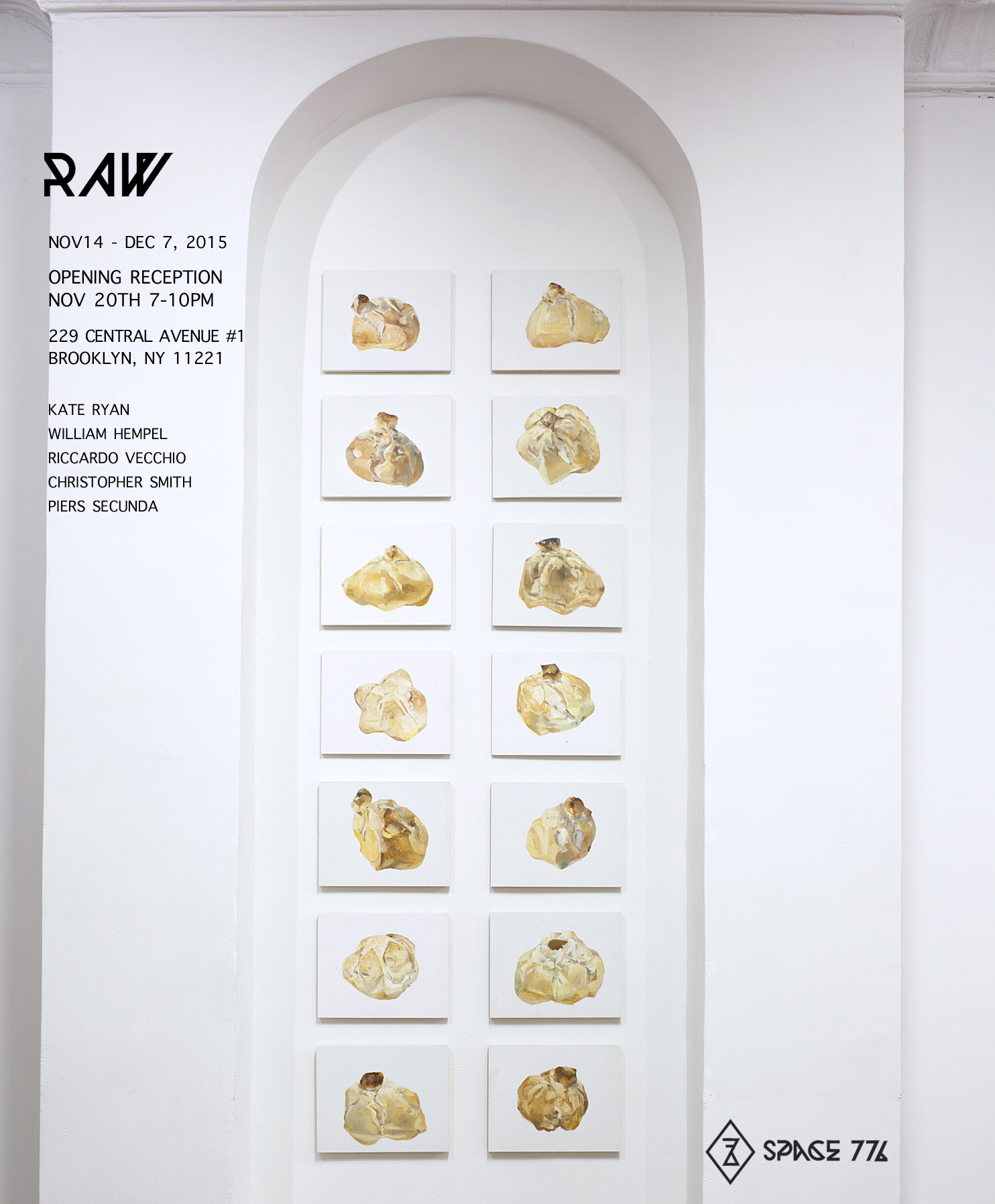

Vecchio paints many of the infamous World War I battlegrounds high in the Dolomites where the Kingdom of Italy and the Austro Hungarian Empire clashed between 1915 and 1918. Recent paintings, steeped in those places, are enhanced by satellite imagery and study of topographical maps combined with Vecchio’s oil and pencil sketches made during summer months of hiking and camping in the wilderness to observe and record those locations. Vecchio’s large paintings emphasize another dimension, the universal views of this particular space of conflict in the rocky crags and crests of the mountains. Reanimating history, and using GoogleEarth, Vecchio creates 3-D printed silicone sand models of the places he has walked, and then transforms the physical knowledge of those places into giant paintings, melding memory of place with his experience of hiking, and with images taken from the satellite, his camera, his models, and paintings made en plein air. Using technological advances to inform his views of the mountain ranges, Vecchio’s resulting large-scale paintings approach the vedute from every angle. Adapting techniques familiar from Venetian paintings like Tintoretto’s Last Supper (1592-1594), a painting on canvas at the Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore, in Venice, Vecchio paints as if looking down simultaneously from a bird’s eye view, and across landscapes as if gazing from a nearby peak, and as if standing with feet firmly planted on the ground. Vecchio’s technique bridges human experience of the past, present and future, and his landscapes fall into the tradition of gifted late Renaissance painters, whose predella paintings were often devoted to horizontal landscapes, or the Italian landscape paintings of the nineteenth century, who glorified unadorned aspects of physical nature.

Vecchio also emulates the colors of places he experiences, using photographs to enhance memory, and painted sketches to remind of the experience of the colors---like sunshine on snow, or rain on the bald craggy rocks---in the moment he saw them. This technique combines an understanding of a historical moment with the experience of that place seen a hundred years later. Shattered stripes of light seem to cloak the mountains in Vecchio’s more recent and large-scale paintings, giving a fresh impression of the fragmented landscapes he has traveled.

Kikki Ghezzi is an experiential artist, creating installations and paintings that interpret poignant memories of her childhood in Milan and in the village of Bormio, along with more recent vivid works of universal appeal, exploring the connection through three generations of Italian women. Her work relies upon memory as inspiration, as she shares spiritual and often metaphysical realities. The 24 Ore refer to the contents of a briefcase, designed to hold the day’s essentials. Filled with prints in a variety of colors, the 24 Ore hold literal impressions, in printed form, of the interiors of her family’s home in Italy. In the last of three valises, Ghezzi placed a sealed letter to her parents, a sort of memorial to her family and upbringing, after their deaths. The spiritual qualities of Ghezzi’s work, both meditative and contemplative, offer the viewer an opportunity to pause and reflect upon their own connections to family and the past, in a quiet way, with the metaphorical embrace of a daily briefcase to hold and contain thoughts of the day. Ghezzi excels in finding the universal voice in the personal.

Using the hand-embroidered linens, pillowcases, and sheets handed down to her from her mother and grandmother, Ghezzi brings together the personal and historical threads that literally connect these three generations, and presents these works in fresh fashion to a new contemporary audience.

Lisa A. Banner is Adjunct Associate Professor of Art History at Pratt Institute. She is curator of an ongoing series of contemporary exhibitions at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, in the James B. Duke House [www.bit.ly/IFAdisplay]. As an independent scholar and curator, she has organized exhibitions like “The President’s Face,” highlighting loans from private collections with rare photographs of Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and James B. Garfield, at the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library. She is a frequent invited lecturer at places like The Courtauld Institute, The Frick Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Meadows Museum, and elsewhere. In 2014, she curated a contemporary art installation at Prospect 3+ Biennial, New Orleans. Since 2013 she has curated contemporary exhibitions at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU [www.bit.ly/IFAdisplay]. Her latest exhibition, SHIFT: Jongil Ma, Christopher Smith, Corban Walker was on view at the David Owsley Museum of Art. Banner is also a board member of The Hammond Museum and Japanese Stroll Garden, and a member of the Research Programming Group at the Frick Art Reference Library.